Change has gotta come…

Logan Webb’s change-up was considered one of the best pitches in baseball in 2023. He threw more than 40% of the time and served as the horse he rode to a runner-up finish in the National League Cy Young voting. Its 28 Run Value was the second highest total of any pitch type across the Majors. Compared to other offspeed offerings, Merrill Kelly’s 16 RV was the next highest RV total.

In 2024, the dominance that we — and probably Webb as well — took for granted with his signature pitch disappeared. The change-up’s year end Run Value had dropped into the negatives, a rough plummet from the best in the league penthouse to the dark, dank cellar of the 14th percentile. A shocking turn of events that has to be one of the largest year-to-year swings in the league, reflected his highest marks in ERA (3.47) and xERA (4.31) since 2021, his first full season with the San Francisco Giants.

There were signs pointing to this breakdown. Opponent’s hard-hit rate has increased steadily since Webb became a rotation stalwart — rising from 38.5% in 2021 to 44% in 2023 to 51.6% in 2024. Average exit velocity and barrel rate showed similar increased rates. Webb has never been one to avoid contact completely, or shy away from hard contact. He survives and thrives thanks to how he dictates the meeting of bat and ball. A ball hit hard but driven into the ground might find an infield hole, might squeeze between the bag and a glove, burying itself in an outfield corner, but it will never leave the park. As Grant Brisbee pointed out in his recent article (again…I’m a day late), the moment the baseball collides with the unyielding dirt in front of home plate, or drags along countless blades of grass, it starts to lose its initial explosiveness, becoming a much more manageable beast by the time it rolls 90, 95, 100 feet across the infield.

So the problematic quality of contact rates are mitigated by the excellent groundball rate the Webb’s change-up produces. But what seems to have happened in 2024 is hitters were much better at getting under the pitch. The average launch angle shot up from -5 degrees (about where it was since ‘21) to 4 degrees. A 9 degree leap that produced more balls in the air. Once airborne their potential for extra bases and greater damage grew. Ground ball rates dropped while batting and slugging averages rose. 9 of the 11 homers Webb gave up in 2024 were off his change-up.

Perhaps what is most telling is where the baseball went after it made that fateful transformation from pitch to batted ball. Opponents pulled the change-up 39.1% of the time in 2024 — the lowest percentage in Webb’s career. Normally preventing a player from directing contact to their power side is a win for the pitcher, but the change-up is different. Trying to pull the heavy and drooping offspeed often results in “rolling over” it, producing a flat reedy sound as the ball connects with the bat and becomes a toothless routine grounder. Last season, though, hitters got smart. They adjusted and started getting batting the offering up the middle or sending it the opposite way. All this success reflects a more focused and nuanced approach against the offspeed. Opponents looked for the pitch, identified it, and redirected it. They chased it out of the zone more than ever but they also put those balls in play more than ever.

This is the burden of success. Webb became synonymous with the change-up — he threw it more than 40% of the time, the most in his career, in 2023 — and every pregame hitters’ meeting in the opposing clubhouse in 2024 started with an in-depth discussion on how to counter it. I was at Fenway when the Red Sox ripped seven of their nine hits (tied for his season high) off Webb’s change-up. Six of those hits were shot back up the middle or punched into the opposite field. Six of those hits left the bat with an exit velocity of 95 MPH or higher, and five of those had a velocity higher than 107 MPH. Hundreds of feet away, ten rows up from the bullpens in right field, I was rattled. The bright crack of their contact reverberated in my ears. Imagine how Webb felt, his legs jelly on uncertain ground as he walked off the mound in the 4th inning after Wilyer Abreu’s 114 MPH RBI triple. Another change-up obliterated.

After a month of getting knocked around, an adjustment had to be made. The 40% change-up pitch usage in April dropped to 32% in May. Apart from a brief spike in August that downward trend continued, bottoming out at 20% in September as Webb began to experiment with his cutter against lefties. He needed something new, a new speed and shape especially against lefties, to help aid his offspeed. It didn’t really help. Opponents batted and battered it around like a cat with a cork, hitting .435 with an .870 SLG.

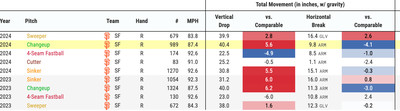

Obviously, Webb has expressed frustration with how the pitch performed last year. Though the league took some serious strides, it wasn’t just an improved plate approach that sent the pitch spiraling. Something was off. Something was weird, an apt word for the change-up’s mercurial nature. On the surface though, there was nothing noticeably problematic. Nothing as obvious as lack of command, leaving the pitch up in the zone, or throwing with his left arm instead of his right. Webb did mention to Andrew Baggarly that he made a minor grip adjustment to “restore some of its familiar fading action.” Though the induced movement between 2023 and 2024 seem pretty comparable, there is an inch-and-a-half of lost horizontal run evident in the year-to-year numbers.

Tweak the grip. Increase the arm angle by a degree or two. A game of inches indeed. Chalk up the offspeed’s down year to one of life’s many vicissitudes. The only constant is change, and sometimes that change gets smoked into the left-center gap.

What we learned about Webb is that he has other means to get batters out. Considerably winged, he still made himself invaluable to the Giants by way of emphasizing his fastball. The choice hitters made by attacking the offspeed meant they were exposed to the sinker, which accrued a 17 Run Value, just a notch below Rookie of the Year Paul Skenes’s mark and good for third highest in the Majors. His ground ball rate took a hit from last year thanks to that improved launch angle, but it was a minor one and he still placed in the 95th percentile. He still stayed healthy, started 33 games, and led the National League in innings.

Even with the change-up off the mark, Webb could still fulfill plenty of the club’s needs — but was he still Webb? Like Webby Webb Webb? I don’t think he felt completely himself last year with so much doubt swirling around his signature pitch — those lined singles shot the opposite way in Boston might still be eating away at him. No, Webb doesn’t necessarily need the change-up operating at a high level to “get the job done” — he just won’t be great.