Sometimes good things happen.

Put the ball in play.

It’s an adage we’ve all heard since our Little League days, usually accompanied by a comforting hand on the shoulder after a tough 0-fer.

“Hey, at least you put the ball in play, son.”

“Yeah…but it’s T-Ball, dad.”

Looking beyond results or quality of contact, it’s comforting knowing you at least performed the essential task as a hitter: I hit the ball. Sometimes it’s all you can do.

The phrase’s virtues were expounded from the broadcast booth last night. Duane Kuiper and Mike Krukow have been around the game long enough (and still recovering from and processing the conditions at Candlestick) to know how much of a headache a baseball in motion can be. 100+ MPH line drives are one thing, but defenses practice handling that kind of contact because that’s the kind of contact that will statistically hurt the most. Fielding well-struck grounders or deep flies may come with a higher expected batting average, but their paths are often predictable, allowing a fielder to stay in rhythm when approaching the ball and corralling it. But when someone talks about putting the ball in play they aren’t talking about scorchers or screamers, they’re talking about squibbers and high-hoppers and dying quails and flares and mile-high pops. Situational hitting at its most fundamental: Did you hit the ball? Did you make the defense make a play?

Hitting a rock with a stick is an odd thing. A weird collision of different textured and shaped surfaces with varying measurements of energy and matter that can produce some real unpredictable results. That’s the main attraction: it scratches some primitive itch. The first shepherd, bored out in the hills, who tossed a stone up in the air and hacked at it, finding it with the barrel of his rook, hearing the round note of the collision, watching the stone spin out into the beyond.

Put the baseball into the world, and who knows what will happen. The wind changes. The ground isn’t flat. To throw another aphorism at ya, to err is human. There’s nine flawed flesh bags out there overly-excited to chase after a moving ball and supremely capable of screwing things up. It might be a more straightforward ball in play, but the moment a human being gets involved (meaning: an idiot) all bets are off. A decision has to be made, a task performed. Sometimes they choose to do silly things, or awkward things, or well-intended but ill-advised things.

In the case of Monday’s series opener between the San Francisco Giants and Philadelphia Phillies — a 3-1 win for the good guys — balls in play fueled the night’s scant offensive production.

Both starters Landen Roupp and lefty Cristopher Sánchez have been excellent at avoiding hard contact all season long and performed as advertised in their head-to-head match-up.

Though ultimately done in by pitch count after the 5th, Roupp mixed his pitches well. Despite getting just four whiffs from Philly hitters, he stole 25 strikes, including 16 with his sinker. He lacked the wipe-out stuff to dispatch opponents more efficiently, but he still did well to maintain count leverage, generate ground balls and avoid a lot of worrying traffic on the bases.

How Cristopher Sánchez is going to attack a hitter is no secret. The lefty has a dominant power change-up. It’s accrued a 9 Run Value already, putting his offspeed offering in the 99th percentile of the league. His mix is pretty much 40 – 40 sinker and change, with a cheeky slider on the slide to keep things fresh. But in a two-strike count, a hitter knows what is coming…and it’s still pretty much un-hittable.

The pitching lived up to the billing. Both starters surrendered a single run each, and both runs that came around to score were certainly not products of convincing contact. Neither team had a hit with runners in scoring position all game (15 ABs total).

The Giants scratched their lone run across in the 2nd. They loaded the bases with nobody out after Matt Chapman and Wilmer Flores both punched sinkers through the infield for singles, and Casey Schmitt, in his return from the IL and starting at second base, refused to bite at five consecutive offerings just missing the bottom of the zone. But Sánchez got back in the inning with a strikeout of Jung Hoo Lee (which has got to be one of the more uncomfortable at-bats left-on-left) that opened up a number of off-ramps. He had struck out a dozen in his previous win against the Giants in April and his 26.2 K% is in the 75th percentile — so carving his way through Luis Matos and Patrick Bailey seemed more than plausible. Or there’s the good ol’ ground ball. Opponents’ grounder rate off Sánchez teases 60%. An easy roller at an infielder would either produce an easy fielder’s choice out at home or an inning ending double play.

Off the bat, that’s exactly what Matos’s ground ball appeared to be. A slow hopper to the left of second base, right in the path of shortstop Trea Turner to field, toss to second, and initiate the double play…

PUT THE BALL IN PLAY and open yourself up to a kaleidoscope of strange and wonderful possibilities. In a 1-2 count, Sánchez executed a perfect change-up low and away and somehow Matos got enough of a chunk, allowing Turner — good ol’ Trea — to do his thing.

San Francisco nearly edged ahead at the expense of the Philly defense when Rafael Devers skied a fly ball to shallow left that started to do funny things. Second baseman Bryson Stott twisted and turned, trying to settle under it, before plummeting safely to the outfield grass between him and the charging right-fielder Nick Castellanos. Kuip, having lived that experience and holds both empathy and disdain for poor performance on the pop-up dance, quipped that the baseball was in the air for three-minutes. More like 6-seconds — still plenty of height for the wind to toss it around like a pair of shoes tumbling around a dryer.

But just as a disproportionate amount of breaks were going the Giants’ way, the world self-corrected, and because we live on a level playing field and exist in a karmic universe where balance and justice reign (…) “luck” — or whatever you want to call it — started to hold sway for the Phillies.

They certainly caught a break on a 107 MPH drive off the bat of Matt Chapman that knuckled in the air and sent center fielder Brandon Marsh spinning trying to reel it in. With a two-out jump, even Devers, who runs about as fast as a turtle with a groin strain, would’ve scored easily from first. He was halfway to home before he realized to pull up and return to third — the ball had skipped hard off the warning track, ricocheted off the padded corner of the wall in straightaway center before dropping into the visiting bullpen, out of play. It was the one hit of the game that deserved to bat in a run, and it didn’t. Marsh remained on his knees, offering up a humble prayer of thanks to the powers that be.

A friendly hop held the Giants’ lead to one in the 3rd, and another one helped the Phillies to tie it in the 5th.

This is how the hit in question was described in the game log: Bryson Stott doubles on a ground ball to second baseman Casey Schmitt, deflected by first baseman Wilmer Flores. This is how I’d describe it: Bryson Stott rolls routine grounder towards first baseman, Wilmer Flores, ball skips due to glitch in the matrix, kicking off phantom wrinkle in grass to avoid first baseman Wilmer Flores’s glove, then pinballs off the instep of first baseman Wilmer Flores’s foot into foul territory to be chased down by second baseman Casey Schmitt, Bryson Stott to 2nd, scorekeeper can’t decide on hit or error because it is neither, snaps official scorekeeping pencil in half and walks out of booth, official ruling pending.

Ball in play. The “double” would be the Philly’s only extra base hit of the evening, and Stott would come around to tie the game by advancing to third on a groundout before scoring on a wild pitch from Roupp.

The score remained knotted at one-run a piece until the 8th. Sánchez breezed through the 7th inning, while Ryan Walker, Joey Lucchessi and Tyler Rogers handled the next three frames for the Giants after Roupp’s departure.

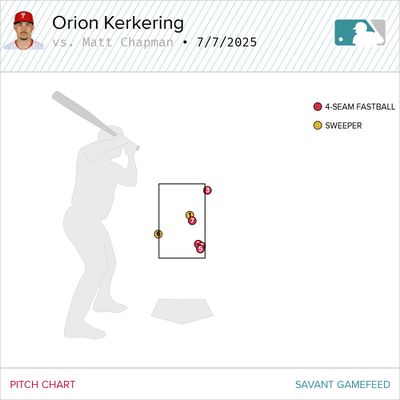

With Sánchez out of the game in the 8th, the Phillies bullpen took over and things shifted again. The universe’s scales started to tilt back towards the Giants. Right-handed reliever Orion Kerkering lead-off the frame by hitting Willy Adames, and then out of nowhere Phil Cuzzi started to shower Chapman with gifts in the zone. Three straight fastballs all painted on the outside edge that could have easily been strikes 3, 4 and 5 were called balls.

A welcome back present from Cuzzi that Chapman didn’t take for granted. On the 7th pitch, he shot a fastball over the middle of the plate (because it had to be) through a hole in the right side of the infield, setting up runners at the corners. Kerkering, understandably confused about where the baseball should go, plunked Flores to load the bases for Casey Schmitt.

Schmitt was clearly happy to be back on the diamond. He had walked to set-up the Giants first run in the 2nd, he singled in the 6th, and with a chance to knock in the go-ahead run, Schmitt drove a heavy sinker from Kerkering directly into the ground. But you know what — he put the ball in play, and that ball in play, in another 2-strike count, was the perfect amount of weird to get the job done. It forced Turner just enough to his left to take away a play at home. And with the pulled-in infield, getting the out at second was awkward and slow in developing, providing enough time for Schmitt to hustle down the line and prevent the double play.

Legging it down to first proved consequential because with two outs, the infield could’ve decamped from the cut of the grass. But because the bases were still loaded with less than two outs, they had to stay in, forcing Bryce Harper to make another awkward play on another ball on the ground in an attempt to prevent San Francisco’s third run from scoring.

Three ground balls — all in two-strike counts, all hit right at infielders — but just funky enough for three runs.

Put the ball in play, kids.

Disclaimer: This is also what could happen if you put the ball in play after you battle for 13 pitches, fouling off 8 offerings in a two-strike count, and absolutely deserve a base hit.

The world owes you nothing.