If you’re coming to San Francisco to see a Giants game… definitely check out these other things the city has to offer.

Welcome to San Francisco. Now leave it.

Every visit to the City on a Giants gameday should begin at the end. So head to the nearest BART stop and take the train to…

Stop 1: Colma

Once, driving to San Diego from Oakland, my serpentine belt in my 1999 Chevrolet Venture van gave out traversing the Grapevine near Pyramid Lake. I coasted down the incline into Castaic and pulled into the first auto shop off I-5. After a couple hours of waiting while watching the 2020 ALCS (Tampa vs Houston, I don’t remember what game), the van was fixed, and as the mechanic pulled the car to the front, the front desk attendant walked me through the work done and the subsequent costs. As I handed over my card he told me that he too was from the Bay, from Colma. I told him that is where my great-grandparents and great-great grandparents are buried, and he nodded, handing me my receipt, and said That is where everyone is buried.

Photo by Graphic House/Archive Photos/Getty Images

It’s true. Colma is a ghost town tucked in a small valley east of 280 and cast in the morning shadow of San Bruno Mountain. It is a necropolis with a Kohls department store and a Kia dealership.

Permanent settlement in the area began post-gold rush with agriculture and a stop on the train down to San Jose. The community began to grow when San Francisco outlawed further interments within the city limits in 1900 and then boomed when the government began to evict dead tenants, beginning a decades long funeral procession south from San Francisco to Colma.

There are 16 cemeteries bedded in its two square miles of land jammed between Daly City and South San Francisco. It is said that the dead outnumber the living in Colma a thousand to one. At the bottom of the town website, the nickname “City of Souls” is written in a soulless font, under it, a soulful slogan: “It’s great to be alive in Colma.”

Joe DiMaggio is not alive in Colma. He is dead. This is the beginning of our tour.

Heading south on El Camino Real from the Colma BART stop, the Hall of Famer and native San Franciscan is buried not in the Italian Cemetery, marked by a massive blue boot on the boundary wall, not in Woodlawn Memorial Park or Cypress Lawn where Lefty O’Doul and Willie McCovey are laid to rest, but in Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery. To get the Yankee Clipper’s final resting place you go up the long central drive, go around the Googie-stylized receiving chapel, and before the second rotary, turn left to find the patch of grass where DiMaggio’s handsome black marble headstone sits.

Of course, the Yankee Clipper was never a Giant, though it is impossible to talk about the history of baseball in San Francisco without talking about DiMaggio. He shared a city with the Giants in more ways than one. His exploits on San Francisco sandlots and professional fields predates Major League baseball in the Bay by decades. As a 17 year old, vouched for by his older brother Vince, Joe debuted for the Pacific Coast League Seals in October of 1932. In his first full season, he hit safely in 61 games, a PCL record, while hitting .340 over 187 games. Eight years before the nation became transfixed by DiMaggio’s hitting streak for the Yankees, San Francisco bore witness to greatness by this lanky son-of-a-fisherman from North Beach. Like many things, greatness spawned in the West, but was not legitimized until confirmed by the East.

Starting in 1936, Joe’s entire Major League career was spent in New York, with Yankee Stadium, a hop, skip, and a jump over the Harlem River from the Giants’s Polo Grounds. He played 17 games against the Giants (tied with the Brooklyn Dodgers for the most of any National League opponent) spread across three World Series victories. His last professional game came in game 6 of the 1951 World Series — he went 1-for-2 with a double and a run scored in a 4-3 win that clinched the championship for the Yankees.

Limping and in pain from nagging injuries to his legs in that fateful ‘51, DiMaggio still patrolled center. The legend goes that Yankee manager Casey Stengal advised a young Mickey Mantle playing right-field to run down everything he could reach to ease the workload of the elder statesman. A brief that proved fateful when Mickey Mantle, chasing after a flyball to right-ish center, saw that DiMaggio had settled under it, pulled up short and tripped. A cleat caught on a half-buried piece of the sprinkler system, something popped in his knee, and he’d be sidelined for the rest of the series and play through pain, much like DiMaggio did, for the rest of his Hall of Fame career.

The person who hit that routine fly ball? A young Willie Mays. With that consequential yet mundane moment, on that popped ember to the outfield, a torch was passed, a way forward lit. Mays and DiMaggio became linked: Rookie and retiree, fan and idol, opposing poles when arguing for the best center fielder to ever play the game, and two generational beacons of West Coast baseball.

Who would Willie Mays have been without the grace, dignity and elegance personified by DiMaggio? Who would the Giants be without the years of joy and the elevation of that dignity carried on by Mays? What would San Francisco be without the Giants? Who would Joe DiMaggio be without San Francisco?

And what do you do when you visit a grave?

When I went there in March, five days after the 26th anniversary of DiMaggio’s death (he passed March 8th, 1999), and about two weeks before the 2025 season kicked off in Cincinnati, a handful of baseballs were placed at the foot of the headstone instead of flowers. In pictures, this bouquet is constant, often accompanied by a bat. When I visited Babe Ruth’s grave just north of New York City three summers ago, there were baseballs too, as well as a bottle of beer. The Giants were in desperate need of some pep, so I offered up a Brandon Crawford baseball card that I had in my wallet to the Babe. The Hail Mary produced little in terms of tangible results, but I don’t think it hurt the soul either.

So on gameday, head to Colma. But do it right. Go early, when it’s overcast, the sky moody and low from the morning fog. Drape a Jung Hoo Lee Hello Kitty giveaway jersey at Joe’s altar, pray for Adames’ uppercut, Chapman’s hand, light a candle for Devers. Kneel down, repeat Vamos Ramos 17 times then bat flip the Louisville Slugger you brought before walking away.

Where to eat?

There’s a Costco across Mission Boulevard. Grab a chicken bake.

Stop 2: San Bruno Mountain

Now that you have considered death, raise yourself up from this chthonian state and seek the high places. Fall back into the history of this region as you clamber up one the creek-dug ravines, then pace the four-mile long summit ridge line that peaks at 1,300 feet above sea level.

Shellmound burial grounds at the foot of San Bruno Mountain provide evidence of human habitation dating back five thousand years, earlier than the construction of Khufu’s Great Pyramid of Giza. Varieties of manzanita, lichen, flowering plants and butterflies found in the park are holdouts of Bay Area’s original ecosystem. The park is a fossil and a living organism, an active battleground and a celebration of preservation having been for centuries the setting of fires and faultlines, of invasive propagation, colonization and escape, of development and sprawl. Yet there it is: a mountain, undeniably so. Past and present collide in this 2,000 acre reserve. From its heights you can hold it all in your eye — the rust orange towers of the Golden Gate down to the flat spit of land jutting out into the bay. This is why we’re here. This vantage point gives us perspective at the leveled lot. The triumph and folly of man-made things, and no place represents that more than the Giants tenure at Candlestick.

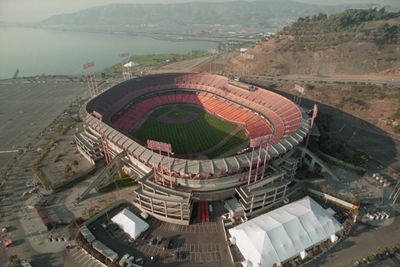

Photo by Duke Downey/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images

These flawed structures are usually castles to one man’s shortsightedness and odd whims. Horace Stoneham, who after decades dealing with the out-dated oddities of the Polo Grounds in cramped northern Manhattan, was dead-set on the Giants playing in a modern park —which meant a field inconvenient to get to and ensconced in pavement. Parking, he was obsessed with parking, and what sold him on the idea of moving his club to San Francisco was the parking paradise that the Bayview spot promised. Construction was corrupt, delayed, corners were cut. The realization that what was promised was not what was produced came as quickly and as violently as a change in winds. The Giants fielded some of the best teams in club history and put together their most prolific decade, yet won just one pennant. The cold air and gust knocked down would-be homers while chilling fans to the bone. Displeasure in the grounds was apocalyptic, seismic. The Columbus Day Storm of 1962 flooded the field, and postponed game six of the World Series for four days. They say the outfield was still soaked for game seven and the damp sloggy conditions slowed the hard-hit baseball as it rolled towards the right field corner in the 9th, allowing Roger Maris to cut it off before it reached the wall while freezing Matty Alou as the tying run at third and Willie Mays at second. During the Loma Prieta earthquake in ‘89 the stadium’s concrete shook and swayed but did not break. The lengthy postponement of game 3 allowed Oakland’s Tony La Russa to reset his rotation and roll out ace Dave Stewart, who held the Giants scoreless in game 1. He’d give up 3 runs over 7 innings pitched in the A’s 13-7 rout.

Forty years roll in and burn off as quick as the marine layer at this elevation. We have to shake our heads and smile at such a variety of experience: Richard Nixon’s first pitch, natural disaster, The Beatles final U.S. concert, Crazy Crab, out-of-state buyers, Juan Marichal’s leg kick, Johnnie LeMaster, Hummm Baby, World Series drama, Barry Bonds — all came for the Giants when they called Candlestick their home.

Where to eat?

Head back down on Guadalupe Canyon Parkway, there’s In-N-Out not far from the Colma BART station. Don’t forget grilled onions!

Stop 3: Potrero Center Strip Mall

The Giants were baptized San Franciscan on April 15th, 1958. Right-hander Rubén Gómez struck out Dodger center fielder Gino Cimoli in the club’s first on-field act on the West Coast. In front of 22,000 people lining the stands at Seals Stadium, the rechristened Giants won 8-0. Gómez would go on to throw a complete game shutout, giving up 6 hits, 6 walks while recording 6 Ks.

Photo By Gordon Peters/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images

You can still walk these grounds — they just aren’t a baseball field anymore. There’s no rubber to toe or box to dig into, just cheap carpet or linoleum. Seals Stadium (opened in 1931), considered a crown jewel of PCL parks, was unceremoniously demolished two months after the 1959 season ended, gone the way of the first Recreation Park destroyed in the 1906 earthquake, Ewing Field, as ur-Candlestick, lost in the fog, the second “Big” Rec. Home plate was torn from the ground like a rooted tooth, the concrete grandstand razed, the right field wall and bleachers running along 16th street flattened and opened to traffic. The city block in the Potrero Hill neighborhood has been a shopping center for awhile now.

Home plate would’ve sat somewhere in the fluorescent lit commercial space for lease. First base, out front on the curb just beyond the automatic doors; second and third 90 feet apart somewhere in the grocery aisles of the Safeway.

Another paradise paved — but perhaps this too can be redeemed slightly by the small rituals that bind all fans.

Pace out the infield and dodge shoppers as you round those bases. Throw a tennis ball against the stuccoed front of the Ross Dress For Less. Play pickle between the cart corrals, toss fly balls over the Teslas and Priuses in the parking lot that used to be right and center field, the wide-open plain Willie Mays and the citizens of San Francisco met.

Photo by Joe Rosenthal/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images

Where to eat?

Grab a Mango-a-go-go smoothie from Jamba Juice and you’re good to a-go-go!

Stop 4: Mission Creek

Photo By Santiago Mejia/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images

Oracle Park sits about a mile and a half northeast from where old Seals Stadium once was. It seems appropriate after this day of rumination to approach the present humbly. Not by Lyft or driverless cab, but by your own power. You could hoof it down Townsend, but taking to the waters feels like a more appropriate mode for this final leg. Put in your vessel at the Mission Creek Kayak Launch and paddle up the channel out to McCovey Cove. As you float out there, waiting (probably in vain) for a Rafael Devers splash hit, consider the shifting sands and rising waters we build on. How long will Oracle last? When this world is finished, the hermits will wait for the waters to recede from the peak of San Bruno, and debate how to move forward, what to build, where to dig their feet into the ground and proclaim, “This is home.”

Photo by Jerry Driendl/Getty Images

Where to eat?

Ask that guy with the grill on the back of his kayak for a hot dog.